|

| Childhood and youth in New Zealand and Sydney |

|

| Baby Peter with father Lewis and mother Lily -Wellington, New Zealand |

Peter Francis Nicholas Deli was born

on 26 March 1942 in Wellington, New Zealand. His parents, Lewis and Lily,

were both Hungarian refugees who had fled Europe just before the beginning

of the War. His father, an architect by training, had been a violinist

in the Budapest Symphony Orchestra. His mother, who was Jewish, had tried

to emigrate to Britain and Australia before settling for New Zealand.

They met in New Zealand and married in 1941. After the War the Deli family

moved to Sydney, Australia and settled in the Eastern Suburbs at Bondi.

Sydney had a much larger population of East European ![]() migr

migr![]() s

than the whole of New Zealand and the Delis were soon absorbed into the

Hungarian community's protective embrace. Peter's early school years at

Double Bay Primary School were far from typical of the elementary educational

experience of most Australian children at the time. The extraordinary

mix of nationalities and class backgrounds in the school must have had

a profound effect on his early development. In 1955 he won a place to

the prestigious Sydney Boys' High School, one of the best secondary schools

in New South Wales. Peter excelled in his studies during these years and

matriculated with honours to the University of Sydney in 1960. During

his undergraduate years he read History and Philosophy, graduating Bachelor

of Arts with First Class Honours in History in 1964.

s

than the whole of New Zealand and the Delis were soon absorbed into the

Hungarian community's protective embrace. Peter's early school years at

Double Bay Primary School were far from typical of the elementary educational

experience of most Australian children at the time. The extraordinary

mix of nationalities and class backgrounds in the school must have had

a profound effect on his early development. In 1955 he won a place to

the prestigious Sydney Boys' High School, one of the best secondary schools

in New South Wales. Peter excelled in his studies during these years and

matriculated with honours to the University of Sydney in 1960. During

his undergraduate years he read History and Philosophy, graduating Bachelor

of Arts with First Class Honours in History in 1964.

Peter was not part of any established campus institutions during his time at Sydney University. They were the preserve of socialites and student politicians and were therefore way beneath the sub-culture in which Peter dwelled. Peter disliked any sort of organised activity. He did however take an active interest in The Push, although he was never part of it. He knew the Push's Hungarian member George Molnar very well, but the movement really predated Peter's generation of student activists. Peter instead gathered around him an eclectic and eccentric collection of friends, many of them radically-minded like himself, but not all of them. This group included his closest friend Myron Kofman. Many of them were, like Peter, attempting to throw off some of their middle class upbringing. Clive Kessler, Chris Conybeare, Bob Connell, Maureen Tighe, Josie Jeffrey and Nina Gantman were among them. Outside the university he collected a gallery of social misfits around him. It was one of these, the 'Bulgarian anarchist friend', Jack Goncharoff, who became a major influence on him during his later years at Sydney University. Upon graduation Peter decided to enter the postgraduate Master of Arts programme at Sydney University and began three years of research (1964-67) focusing on Stalinist Russia. During this time he secured his first university appointment, lecturing on nineteenth and twentieth-century European and British history at the University of New South Wales during 1966. He found himself in trouble almost immediately, however, falling foul of Professor Frank Crowley, the doyen of Australian historians at UNSW, because of his long-held and vociferously expressed views on the dullness of Australian History. His M.A. dissertation 'The Russian Purges 1936-39: Their Image in the Contemporary British Press and their Significance in Historical Perspective' was awarded First Class Honours and Peter was recommended for the Gold Medal. It was no surprise to his fellow students and teachers that Peter wanted to further his studies after the M.A., but his decision to go to Oxford and read for the D.Phil. in 1967 was an unexpected choice of university.

![]()

Peter went to school with mother

| Oxford days |

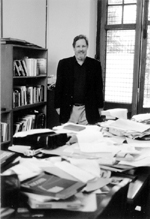

Peter was one of the generation of bright young Sydney and Melbourne intellectuals who found Australia's 'cultural cringe' so stultifying that they opted to travel to Europe in order to explore their cultural heritage rather than settle into middle-class mediocrity in their own 'Lucky Country'. This decision was all the more poignant for Peter as his parents had fled pre-war Europe in the most desperate of circumstances and Peter always thought of himself as not quite Australian but not quite Hungarian either. In many ways his time in Europe was a search for identity, a search which was to last for the rest of his life. He therefore joined the throng of young Australians living in Oxford, Cambridge and London, among them his fellow Sydney University graduates Chris Conybeare and Myron Kofman, and the soon to be famous Clive James and Germaine Greer. But it was rarely the Australians at Oxford to whom Peter was drawn. Many of them tended to ape the middle-class English manners which he so despised at this stage of his life. He very quickly found himself at home in Oxford, however, where his college, St Antony's, was a magnet for people like him who had an interest in contemporary international affairs. His social group consisted almost entirely of a disgruntled band of third world, colonial and radical students who formed an anti-Establishment bloc in the St Antony's Common Room. His closest companions in his first year at Oxford were an 'inner circle' consisting of Jose Cutileiro from Portugal, Andres Bande from Chile, Kubota from Japan and Margaret Macmillan from Canada, but including open-minded English types such as Max Lehmann, Jonathan Israel and Vivian Shue. When this group attempted a takeover of the Common Room Peter was the campaign manager for his friend Andres Bande. The plot failed. Peter's room at Oxford was always a chaotic mess, and Peter has ever since had a capacity for eccentric disorganization which even the casual visitor to his office could not but remark upon. Students found this disorganized approach to his office and lecture notes one of his most endearing characteristics.

St. Antony's College,University of Oxford

Peter's room is the top middle window, Andres' room is the top right one

with the bathroom in the middle

Peter and Andres in the room outside the connecting

bathroom door

Peter with Max and other friends in Oxford

Peter's friends in Oxford: left to right: Ecequiel Gallo, the Argentinian,

Andres Bande, the Chilean, Jose Cutileiro, the Portugese

Peter with the Bishop of Peterborough and the Bishop's daughter

| Happy Paris days |

It was during his first year at Oxford that Peter went to Paris to join

in the excitement of the May 1968 student riots. It was a trip which would

have a lasting impact upon him, for he returned to this vibrant city again

and again in later years. Paris during the student riots of May 1968 was

an intoxicating place for a young man with anarchist leanings and Peter

drank to the full. In many respects it was reflection upon this period

of his life from which Peter gained most pleasure. He had already met

Antoine Dougados while travelling in Greece. Dougados was manager of the

Auberge de Jeunesse, an anarchist-run youth hostel in Laumiere. Peter

visited the hostel on numerous occasions and met lifelong friends from

all walks of life while enjoying good wine and parties. Among these friends

were Roger Mareel ('The Belge'), the multilingual Belgian truck driver

who taught Peter how to pick up girls in cafes; Russ Michaelson, the American

who found himself in trouble with the French police; Antoine's brother

Pierre, the cinema projectionist working in the Quartier Latin; together

with Didi, Buc, Roland, Sylvie, Janine, Christian, Jose Reterra and many

others. Peter was always proud of his ability to move between working-class

Paris and the refined intellectual climate of Oxford with such ease. These

experiences, together with two years of teaching English and American

history to students preparing for admission to the Grandes Ecoles at Lycee

Henri IV (1971-73), helped to form his opinions about his doctoral research

topic: the reaction of the French left to the crisis in the international

Communist movement in Russia and eastern Europe. Under the supervision

of Wilfred Knapp of St Catherine's College Peter's natural qualities as

an intellectual blossomed. Knapp realised that Peter had a temperament

which was sympathetic enough to get on well with the French theorists

but at the same time he possessed a scholarly objectivity which enabled

him to write a critical account of these same French intellectuals. His

eventual D.Phil. dissertation, 'Attitudes of the French Left towards International

Communism as illustrated in the Press with particular reference to the

Russian interventions in Hungary (1956) and Czechoslovakia (1968)', was

a work which the examiners felt was neither entirely historical nor predominantly

political in its approach, but it was completely original. Peter was ultimately

awarded the postgraduate Bachelor of Letters (1975) for his

dissertation, which Oxford converted to a Master of Letters in 1986. It

was during Peter's years in Europe that his father suffered a serious

and paralysing accident which forced him to return to Australia. His father's

accident upset him deeply and he found it a difficult decision when it

finally came time to return to Europe. Once back in Oxford he found life

a battle against financial hardship. Raymond Carr helped him get his job

in Paris and after two years there he was appointed to a temporary lectureship

at the University of Hull, a place which he hated. He found Hull and its

university grey and lifeless, but he proved a popular and valuable member

of the History Department during his year there (1973-74). While at Hull

he taught courses on 'Europe and America from 1776' and 'International

Communism and Western Europe'. With his doctoral dissertation in its final

stages of preparation and a full teaching load at Hull, Peter applied

for and was appointed to a lectureship in History at the University of

Hong Kong in September 1974. He did not want to leave Europe but he needed

the job in Hong Kong.

Peter and Antoine in the Youth Hostel in Paris

Antoine Dougados in one of the gatherings

Peter and Pierre in the Youth Hostel in Paris

Peter and the Belge Roger in the Youth hostel, Paris

Dinner in the working class household in Paris

Peter and Myron Kofman in Venice on holiday in 1968, met Teresa Mc Guiness

and Dierdre Smyth

| Hong Kong days |

|

| Peter joined the History Department of University of Hong Kong in 1974 |

Peter met Jenny within months of arriving in Hong Kong. Introduced to

each other first at 'Scene', the discotheque in the basement of the Peninsula

Hotel, later that night they went to the Senior Common Room Christmas

party at the University. Jenny was a graduate of HKU and was working for

Cathay Pacific Airways at the time. They were married at City Hall on

2 July 1976 and immediately began travelling, first to New Caledonia for

their honeymoon but, within the next year, they had travelled throughout

Europe and had begun to explore Asia. Weekends in Hong Kong during term

time were spent mostly at parties on Lantau with Colin Davies and Nick

Kitchener, and there was a rich social life within the University. Other

friends in these early years included Kevin MacKeown, Geoff Blowers, Jim

Bullen, Brian Young and Mike Summers, but Peter also loved to meet and

debate the issues of the day with Jenny's wide circle of left-wing friends.

Moreover he delighted in the gastronomic pleasures of meetings with Jenny's

school friends and their husbands. The arrival of Louis in 1978 did nothing

to suppress Peter and Jenny's will to explore and Louis became one of

the best-travelled babies on campus from the tender age of three months.

Most summers were spent in France where the Delis based themselves in

Paris, often staying with the Gosselins. One of the most memorable summers

was 1995 when Peter and Jenny found themselves visiting mutual friends

in Paris quite by chance. Peter would do anything to get out of Hong Kong

in those early years. He even attempted to organise a teaching exchange

to New Mexico (of all places!) in 1978. He was less enthusiastic about

the abortive attempt to go on exchange to St Petersburg in 1994 but he

was still looking for new experiences in unexplored parts of the world.

This wanderlust was in many ways a symptom of Peter's inability to come

to terms with life in Hong Kong. He initially found it difficult to adjust

to life outside of Europe. He complained about the lack of good European

films and felt that Hong Kong was little better than Hull in a cultural

sense. But as the years wore on he came to like and even prefer Hong Kong

to the changed places of his youth. He also began to meet kindred spirits

in men such as Joel Thoraval, the French cultural attach![]() .

In later years he cultivated a large circle of French and German friends

in Hong Kong, people such as Denis Meyer, Michel Dupuis, Manfred Kalusa

and Paul Urbanski. They were his constant companions and reminders of

his days in Paris. In recent years he became a founder and committee member

of the Hong Kong and Macau Association of European Studies. He enjoyed

feeling part of the European(as opposed to the British) community in Hong

Kong.

.

In later years he cultivated a large circle of French and German friends

in Hong Kong, people such as Denis Meyer, Michel Dupuis, Manfred Kalusa

and Paul Urbanski. They were his constant companions and reminders of

his days in Paris. In recent years he became a founder and committee member

of the Hong Kong and Macau Association of European Studies. He enjoyed

feeling part of the European(as opposed to the British) community in Hong

Kong.

|

| The father and son, Louis in March 1978 |

Things did not run altogether smoothly during Peter's first days at the University of Hong Kong. The fact that he arrived a month late (thinking that the academic term began in October as it did at Oxford) caused some friction with the head of the Department of History, Len Young, but his colleague Alan Birch took Peter under his wing and guided him through those first difficult months. Peter enjoyed teaching his new students and would in time become one of the best-loved lecturers in the Department of History. His two main areas of teaching from the time he arrived in 1974 until his death were twentieth-century European history and European intellectual history. He also taught courses on 'The History of Communism in Europe' and contributed to courses on 'Early-modern Europe' and 'The Theory and Practice of History'. Perhaps the favourite teaching diversion in his last few years was the opportunity to discuss Homer and Herodotus with final years students taking the theory and practice course. His love of all things (ancient) Greek and Roman is testimony to the catholicity of his tastes when it came to the teaching of history. Another interest which Peter developed very early in his time at the University was the welfare of the undergraduate students. He served on the Joint Consultative Committee almost continuously from 1975 until the time of his final illness and students were constantly coming to him with their problems. He kept photographs of all his classes and religiously added them each year to his enormous collection of personal memorabilia. Peter loved to remember. Peter's colleagues appreciated his unstinting enthusiasm for teaching and his students, and felt that with his irrepressible personal style, he stood in the direct line of descent from the great eccentric teaching historians of Oxford and Cambridge.

|

| Peter and his students outside his office summer 1998 |

Peter was always an inspiring lecturer and gained far more satisfaction

from this side of his professional duties than the minutiae of research

and publication. During his first ten years in Hong Kong, however, he

published a number of articles and a book based on his Oxford and Sydney

research. 'The Soviet Intervention in Czechoslovakia and the French Communist

Press' (1976), 'Jean-Paul Sartre and Hungary 1956' (1979) and 'The Manchester

Guardian and the Soviet Purges, 1936-38' (1984) all appeared in SURVEY:

A Journal of East and West Studies, while 'The Image of the Russian Purges

in the Daily Herald and the New Statesman' was published in the Journal

of Contemporary History in 1985. Peter's book, 'De Budapest a Prague:

les sursauts de la gauche francaise' (Paris, Anthropos) appeared in 1981

but never received the same attention from English readers as it did among

French intellectuals. His research into the evolution of the ideas of

the French left continued throughout his time in Hong Kong and was aided

by research grants to visit France on several occasions to collect materials

for proposed books on subjects as disparate as 'The attitudes of intellectuals

of the Belle Epoque to French Anarchism' and 'The attitudes of contemporary

French intellectuals to the 1991 war in the Persian Gulf'. These projects

did not produce publications but they enriched Peter's lectures and added

an at times surreal dimension to the sparkling discussions in which he

and his friends engaged in the Senior Common Room. Peter was always much

better at talk than writing, but when he did write he was capable of communicating

his keen insights into the politics of the modern world. At the suggestion

of his head of department, Mary Turnbull, he applied for promotion to

senior lectureships in 1987 and 1988, but faced with intense competition

for too few places and having published his book in French (which could

not be adequately evaluated by the Anglophone promotions committee), he

was both times unsuccessful. It seems that these disappointments led Peter

to neglect his research and he instead increasingly focused his attention

on teaching. Unfortunately for Peter the University began changing its

long-term strategies in the second half of his time in Hong Kong. Excellent

teaching and competent administration were no longer good enough in the

new university: 'research' (which was narrowly defined as output of publications)

became for the masters of the higher education sector in Hong Kong the

defining mark of the scholar, as it did in almost every other part of

the English-speaking world. In 1997 Peter suffered the indignity of having

to explain his 'unsatisfactory' research performance in a difficult interview

with Professor Smallman, and this was followed by three years of 'Progress

Review' by a specially constituted committee. This committee's attempts

to 'enhance institutional performance, particularly in the research arena'

in order to 'assist the university in fulfilling its long-term strategic

goals' by scare tactics reminiscent of the totalitarian regimes about

which Peter taught in his undergraduate courses caused a great deal of

personal anguish for those who were unfortunate enough to come within

its unforgiving remit. Peter's long-time distrust of institutions developed

into a loathing of the University's 'Senior Management Team' and in particular

the Vice-Chancellor, Patrick Cheng. It was thus that the last years of

Peter's service at HKU, which should have been a time for proud reflection

upon a good teaching career, were instead blighted by the constant fear

of 'redundancy' on account of the inadequacies imagined by the university

administration. Strangely enough, these final years produced two articles

which, although re-workings of previous research, had an impact upon the

younger generation of media scholars which surprised and delighted Peter.

That younger scholars looked up to him as a pioneer in the field helped

him to come to terms with the difficulties he had experienced at HKU.

'The quality press and the Soviet Union: A case study of the reactions

of the New Statesman, the Manchester Guardian and The Times to Stalin's

Great Purges, 1936-38' (Media History, 5, 1999), and 'Esprit and the Soviet

invasions of Hungary and Czechoslovakia' (Contemporary European History,

9, 2000) were in fact the beginning of a renewed research effort which

also resulted in Peter being

invited to deliver a paper on 'Francois Furet, the French Intelligentsia

and their reactions to Communism in the Soviet Union' at the annual meeting

of the Western Society for French History in California in November 1999.

|

| Peter with Jenny's family in Pine Court -1999 Christmas. Peter's last Christmas party |

Peter took great delight in the events of the last summer at the University of Hong Kong. To him they represented a vindication and a judgment on the people who had played a central role in his own personal hell over the last three years. By that time he had found a degree of contentment with his life. He was happy in his wide circle of friends and had great pride in Louis's achievements. But already the disease which would eventually take his life was showing its first symptoms and Peter's long awaited holiday in Europe turned into a nightmare. He was diagnosed with leukemia while in London in July and had to rush back to Hong Kong from Berlin for treatment. He hated being confined to his room in Queen Mary Hospital and he never became accustomed to the routines of institutionalised living while he awaited the outcome of his course of chemotherapy. When he learned that the treatment had not worked he returned home and was nursed devotedly by Jenny until the very last hours. He passed away exhausted, but at peace with the world, in the early hours of Monday 12 February 2001.

The History Department in 1974

Peter and Jenny - junk trip to Tung Ping Chau

Wedding at the City Hall Marriage Registry

The newly weds tried to decide the sites for photos taking in a very

hot July in 1976

The groom and the best man cum chauffeur in front of Peter's first

car Bakunin

The 3 musketeers at the wedding: left to right: Nick Kitchener, Peter

and Colin Davies with the background of the old colonial Hong Kong Club

and the old Bank of China at the background . The Chinese characters on

top of the bank Are Long Live Chairman Mao

Peter with his 2 aunts in Budapest 1977

The young family in 1978, Middleton Towers

Christmas party with Peter's students

Peter and Louis at Louis high school graduation party

Peter saw Louis off at the airport Louis departed to start College

in Chicago

The Deli family with Mrs. Cheng (nine-nine), the long time helper

at Christmas 1999

Peter got a headache during one of the many boat trips to the islands

Peter with his beloved old Mercedes Benz Durutti. It was the used

car of our friend Ng.